There are dreams that do not belong to sleep.

They wait — behind the noise of cities, inside the quiet spaces of memory — until someone like Stavros happens to pass close enough for them to awaken.

Stavros and the Night of the Emperor

The autumn air in Astoria carried a scent of roasted coffee and old stories. Stavros walked home from the small Greek grocery on Ditmars Boulevard, his canvas bag filled with feta, olives, and a loaf of warm bread wrapped in paper. He liked that the owner still spoke the dialect of his parents—half Cretan, half Macedonian—so that each purchase felt like a little return to somewhere he had never fully lived.

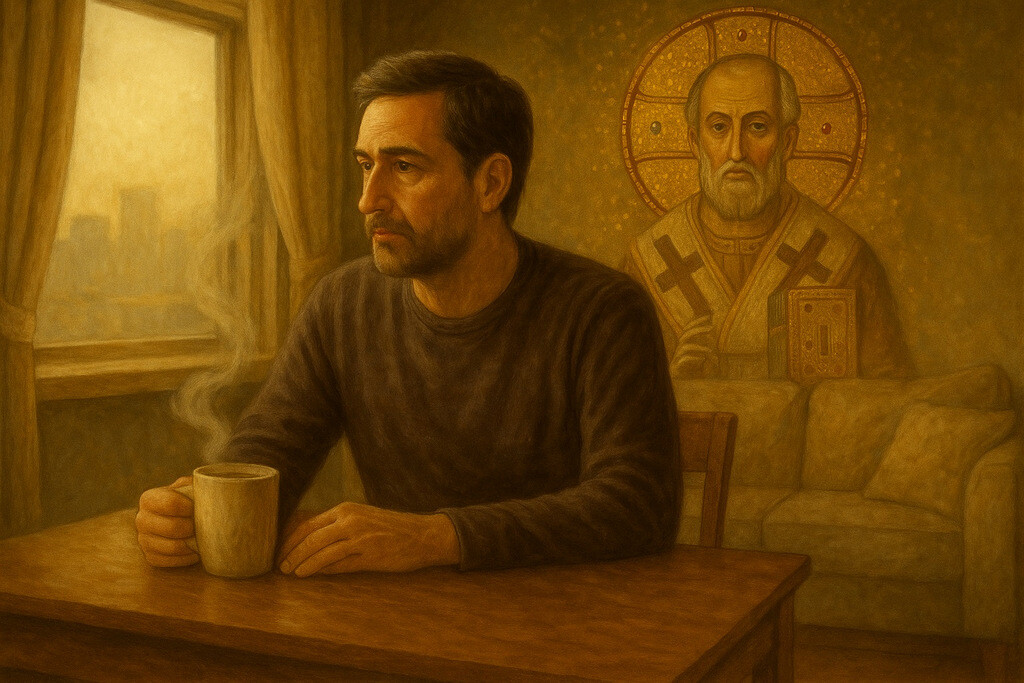

Inside his apartment, the air was thick with memory. On the wall above the kitchen table hung one of his mother’s icons—Saint Nicholas, stern and luminous, the gold leaf slightly cracked with time. The flicker from the streetlight outside made the saint’s eyes seem alive, watching. Beside the icon hung a calendar, its pages already marked with the red circles of his summer hopes: Thessaloniki – Hagios Demetrios, written in careful blue ink. Last year he had gone to Crete, his father’s island. This year he would go north, to his mother’s city, to see the glittering mosaics of the warrior saint and feel again that strange pull between faith and history that had haunted him since childhood.

He placed the groceries on the counter, made a small plate of bread and cheese, and opened the thick paperback that had been living beside his bed for months—John Julius Norwich’s Byzantium: The Apogee. He was at the part where the age of Irene was ending, and the stern, calculating figure of Emperor Nicephorus I had begun to rise. The chronicler’s voice echoed in his mind like a drumbeat: the Emperor marched north, against the Bulgars…

That night, before turning off the light, Stavros allowed himself the smallest of prayers—not to God exactly, but to the dream itself. He wished to see what came next, to step through the parchment of the page and walk with Nicephorus’s men, to feel the clang of armor and the wind from the Balkan mountains.

Sleep took him with the suddenness of a gate closing.

He found himself amid the army, the sky a bruised violet, the banners of the Empire heavy with dew. The Emperor rode ahead, austere and certain. Stavros, a young officer in the dream, felt pride surge in his chest as they crossed into Bulgarian lands. Victory came easily at first; villages fell, gold and captives filled their train. But the mountains grew narrow, the passes darker. A strange silence followed them—no birds, no wind.

Then the ambush came. Arrows like rain, shouts echoing between cliffs. Men fell; horses screamed. The Emperor’s standard vanished in the smoke. Stavros’s heart pounded—he knew this history, knew what was to come, yet could not stop it. The triumph had turned to ruin. When word spread that Nicephorus was dead, the dream itself seemed to shatter like glass.

He woke with a cry, drenched in sweat, the city’s neon light trembling against his wall. For a long time he lay still, hearing only his own heartbeat and the faint hum of the refrigerator. The icon of Saint Nicholas gleamed faintly in the dark, unblinking.

In that silence, Stavros understood: history was not something one read. It was something that reached out from the centuries and claimed you, when you least expected it.

Stavros and the Morning After

The morning light in Astoria crept through the blinds in soft gold lines, falling across the unmade bed and the open pages of Byzantium: The Apogee. Stavros woke with the taste of iron and smoke still clinging to his throat. For a few moments he simply sat there, stunned by how vividly the dream had carried him—not as an observer, but as someone who had lived and fought and nearly died within it.

At breakfast he moved mechanically—boiling water, pouring coffee, slicing a small piece of bread. Yet every motion seemed to echo something from that other world: the ring of armor, the distant cry of men. The smell of coffee turned to the scent of burning timber in his mind, and he could almost see again the wide plains of Bulgaria under the imperial banners.

Fragments returned, wave after wave.

He saw the first victories—how the Byzantines had swept through villages, their discipline dissolving into frenzy once the gates of Pliska were breached. In the dream he had felt both triumph and shame, standing amid the chaos as soldiers looted, burned, and laughed with the savage joy of men unchained. His mind—modern, rational, burdened by centuries of hindsight—had recoiled even as his body obeyed.

He remembered gripping his sword too tightly, watching flames lick the eaves of wooden houses, thinking this will bring ruin upon us. And yet he had marched on with the rest, convincing himself it was only a dream, that his moral disquiet was absurd in the middle of an imagined war. Still, that whisper inside him—the one that had so often warned him in life when things were about to break—was there too, faint but insistent: Nothing built on cruelty endures.

On the subway ride into Manhattan, his reflection in the window looked like two faces layered together: one the New Yorker in a dark coat, earbuds in, briefcase at his side; the other a soldier, dust-covered and trembling, the echo of a lost empire in his eyes.

He saw again the mountains.

The narrow pass.

The sudden eruption of arrows from above—the black rain that tore through the column. Horses rearing, men screaming, the order dissolving into chaos. He remembered the moment he realized he might die; the absurd, almost comic thought that came with it: So this is how history feels from the inside.

And then the panic, the suffocating press of bodies, the desperate crawl through rocks and blood and broken shields until he somehow stumbled free. In that instant, even within the dream, he had forgotten he was dreaming.

When the news spread that Emperor Nicephorus had fallen, a hush had passed through what remained of the army—a silence heavier than battle. Stavros had stood among them, his chest burning with grief and disbelief. The Emperor, once the unshakable figure of power, now a corpse left in the wilderness.

He had seen, too, the wounded Staurakios—dragged on a makeshift litter, his back shattered, his eyes still alive with the grim knowledge that he would inherit a throne he could never sit upon. Stavros had been among the officers ordered to escort him back to Constantinople. The march south had been slow and terrible, through villages that no longer sang, through fields of smoke and the stink of defeat.

Even now, walking the avenues of New York, Stavros felt again the oppressive quiet of that return—the way the men spoke in whispers, the way every hoofbeat on the road sounded like the heartbeat of a dying empire. He could not shake the image of Staurakios, pale and rigid on his litter, the last fragile thread of a future that already felt doomed.

By the time he reached his office, the city had swallowed him again. The noise, the rush, the smell of asphalt after morning rain—it all pulled him back into the present. He smiled faintly, forcing himself to breathe in rhythm with the world around him.

History receded like a tide. The dream’s edges blurred.

He told himself it had only been a trick of the mind—a historian’s fever, born from too many late nights and too much imagination. And yet, as he opened his laptop, a flicker passed through him: not fear, but wonder.

If a dream could carry him so deep into Byzantium—make him feel its glory and its grief as if it were his own—then perhaps history wasn’t dead at all.

Perhaps it was only waiting, just beneath the surface of consciousness, ready to speak again.

Outside, the sun broke through the clouds.

Stavros took a sip of his coffee, steadier now.

He had work to do—and, maybe tonight, another dream to find.

Historical Background

The events Stavros saw in his dream are based on real events in Byzantine history. Below, you can find information about this battle and the emperors.

Battle of Pliska (811)

In 811, Emperor Nicephorus I led a massive Byzantine expedition north against the Bulgars, aiming to crush Khan Krum and secure the Empire’s Balkan frontier. After initial victories and the sack of the Bulgar capital Pliska, the Byzantine army became trapped in the narrow mountain passes during its retreat. Ambushed by Krum’s forces, the army was annihilated. Emperor Nicephorus was killed in battle—the first Byzantine emperor to die on foreign soil in centuries—marking one of the greatest disasters in Byzantine military history.

Emperor Nicephorus I (r. 802–811)

Originally a finance minister, Nicephorus rose to the throne after the deposition of Empress Irene. He was a capable administrator and reformer, strengthening the empire’s fiscal system and reorganizing its military themes. However, his ambition to subdue Bulgaria proved fatal. His decision to invade with overconfidence and poor reconnaissance led to the catastrophic defeat at Pliska. Despite his administrative talents, his reign is remembered primarily for its tragic end and the heavy blow it dealt to Byzantine prestige.

Emperor Staurakios (r. 811)

Staurakios, the son and heir of Nicephorus I, was severely wounded during the retreat from Pliska, suffering a spinal injury that left him paralyzed. He was carried back to Constantinople on a litter and reluctantly proclaimed emperor. His brief reign lasted only a few months, as his injuries made rule impossible. He abdicated in favor of his brother-in-law Michael I Rangabe and retired to a monastery. Staurakios’s fate symbolized the empire’s physical and moral exhaustion after the Pliska disaster—a wounded heir presiding over a wounded empire.

To be continued

As the morning light fades and the city hums awake, Stavros senses that the dream is not over—only paused. Somewhere beyond the veil of sleep, the empire still breathes, waiting for him to return. New echoes of Byzantium—of emperors, saints, and shadows—are gathering, ready to speak again.

Until the next journey, when the dream continues.